How We Redesigned Heap's App in Three Months

Let’s face it: the phrase enterprise web app doesn’t conjure visions of usable, attractive software. Visual design isn’t often a priority: given finite resources and paying customers, the choice between the next big feature and improved aesthetics usually comes down in favor of the feature.

That’s true even at a company like Heap where design is valued. When I joined as VP Design, it was with the recognition of design debt we wouldn’t fix on day one; it just didn’t make sense. Instead, I started a Design Debt backlog that we’d tackle over time, and looked for opportunities where systemic progress could arise out of feature work.

Over the course of 2018 this resulted in numerous UX improvements and some consolidated styles. But it didn’t touch a fundamental problem: our look & feel was dated, and over time—and in the absence of designers—it had fragmented into inconsistency. While there’s no way to quantify how the look & feel affects user sentiment or a prospective sales deal, it was a concern.

So in October I sat down with our CEO, Chief Marketing Officer, Chief Revenue Officer, VP Product, and frontend engineering lead. We agreed this needed to happen at some point, and we thought we had a window of engineering time. We decided to do it!

But our engineering window started within a few weeks, and closed around the end of the year; there wasn’t much time. How could we revamp the look & feel of our entire app, from design to launch, in three months?

The Process

Designing scrappy

No mood boards, no focus groups, no stakeholder interviews: we went from decision to design fast.

But we didn’t want to design in a vacuum. Our two-person design team (our product designer Ray and I) found screenshots of products that might serve as inspiration and perused them. I was intrigued by the simple elegance of Sketch’s dark mode and Blender’s forthcoming redesign; Betterment’s mix of flat, bold lines with sophisticated typography and bright color; and Robinhood’s spare, technical look.

Some sources of inspiration.

Then, we got to work—creating 2-3 styles apiece and mocking up each in a single Heap screen. But where did we get those styles? What would the relationship be with our broader brand as represented on our website?

It would be bold to suggest we ignored all of that and did whatever we wanted. And it might be partly true. But it would also be an oversimplification. Here’s what allowed us to cut those particular corners:

The perfect is the enemy of the good. Here, that meant reminding ourselves that any consistent, clean, modern design system would be an improvement over the status quo. And any such system, once implemented, would be more conducive to its own evolution than what we had. So, a more thorough upfront process might yield something better than a quick-and-dirty one; but the difference wouldn’t be nearly as great as the difference between either approach and what we had.

Data density matters. Products like Heap must show far more data at a far greater density than the average consumer app. That in itself places useful constraints on the design: because we need to let the data shine through, there’s less call for (and strong reasons to avoid) much decoration.

Limit whitespace. Many products, especially in the consumer space, can afford to create visual hierarchy and a sense of calm via whitespace. Not Heap—we have a lot of data to show! So we had to find other ways to achieve those ends.

Our brand is well developed on the Heap marketing site, but that visual language isn’t appropriate to the app itself. So while we took a few cues from it, we felt comfortable ignoring it, too.

Be different. We knew we wanted something modern, but we didn’t just want to look like everything else. So we were hoping to be at least a little distinct.

We had to transcend current functionality. While we weren’t making functional changes, we certainly plan to do so in the coming weeks and months. So we needed a flexible style—one that supported our existing features and would stand the test of new ones. And often, the route to flexibility is through simplicity.

Heap is an app, not a website; a desktop thing, not a mobile thing.

Armed with our five round-one options, we pulled stakeholders into a room and discussed, ultimately selecting one of mine and one of Ray’s.

I didn’t want our final design to feel like it was exclusively mine, or exclusively Ray’s. I’m also a fan of designers working in pairs when possible: the result is stronger than what either would come up with alone. So Ray and I swapped. He did the next iteration of mine and I did his.

And while we did ultimately choose one, that second iteration had caused them to converge…so the choice was less about one distinct style vs. another and more about typography, control style, and color scheme:

Our chosen style: “Eggplant” merged with “Mango,” a.k.a. “Eggo.”

Working in parallel

So, great: we had one mockup. Not a design system. Not a style guide. One mockup. And engineers ready to get started. We’d have to work in parallel, building out the system as they implemented it. That we achieved this without rancor (and with such a high-quality result) is remarkable, and a testament to how collaborative the team is at Heap. A few techniques helped:

Collaboration, not handoff. A lot of ad hoc conversation: on Slack, or swinging by each another’s desks to discuss details as they arose. If we—or our engineers—had insisted on highly polished mocks and specs, this would have taken a lot longer (and been a lot less fun).

Breadth-first design and development: We created a few “hero” screens, then focused on components that exist across the app—leaving one-off UI for last or not at all, especially anything on less important screens. This worked because our engineers implemented our breadth-first changes in a robust enough manner that we avoided “dark corners”: no Heap screen ended up utterly neglected by the project. Not even Settings.

Responsive and flexible attitudes all around. We designed some screens, and some details, that won’t see the light of day and that’s OK. The engineering team had to redo a few things based on designs we just hadn’t gotten to fast enough, and that was OK with them.

Productive stepping on toes. Designers and engineers got into each other’s tools to bridge the gap and avoid messy handoffs: designers working in Web Inspector to explore style details, engineers jumping into Figma to grab our latest work even as we edited it.

This was a re-skin: it left almost everything in its current location. It was hard to resist the temptation to move things around! But we did and it helped tremendously.

The engineering team consolidated as they went, taking multiple definitions of the same style and bringing them together so that a future change (e.g., the next day) would be far easier.

Every project involves compromise; that’s not unique here. What mattered was our ability to be pragmatic together—the corners we cut and the trade-offs we made weren’t done in isolation, or over designer (or engineer) objections. So we could make them more deliberately and in ways that minimized their negative impact on the design.

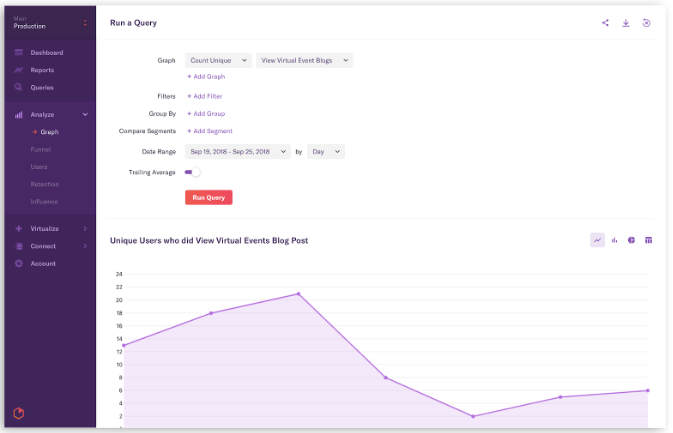

Over the course of the project we refined our style and system, most notably switching from a dark purple to a light gray sidebar. That was Ray’s doing, and it took me a while to get used to—but I love how clean and modern the result looks. And it served as a catalyst for us to go more and more minimalist over time—to keep decoration to a minimum and let the data shine through.

Actual screenshot of Heap today. We might turn that green icon pink.

That minimalism also helped us achieve the goal of feeling clean and open without an overabundance of whitespace. Through incredibly lightweight cards, subtle shades of gray, simple separators, and yes, judicious use of whitespace, we created a modern look & feel that supports reasonable data density.

Preparing for the Worst

Redesigns like this are notorious for their negative response: to existing users they feel like change for its own sake. And because that change calls attention to previously-ignored details, users attribute unrelated, pre-existing issues to it as well: perceived performance drops, even if actual performance is unchanged; and ages-old bugs are suddenly new again.

Visual work is also highly subjective. So inevitably some users just won’t like it—and it’s not like they’re wrong. (Because this is the internet, though, that dislike is expressed as, “Your design team is incompetent and my gerbil could design something better.” The correct response, of course, is to recruit the gerbil.)

Here’s what we did to mitigate potential negativity:

Internal expectation-setting. I was direct about the reception we might receive, because I didn’t want a couple weeks’ hatred to demoralize the team or endanger the project. Mostly this went over fine, but there was some surprise when I said things like, “Best case is nobody notices the change.”

Careful planning with our go-to-market teams (account managers, product marketers, and sales) to give them the context and the time to prepare customers.

Internal “dogfood” launch, to look for bugs and to use employees as a bellwether for customer reactions.

A three-week customer beta with surveys.

The Result

So we were well-prepared for hatred, but we didn’t get it: the reception was overwhelmingly positive. A post-launch, in-product survey asked customers how much they liked the new look, and on average they gave it 7.6 out of 10. (If that seems low, recall that “nobody notices” was an acceptable outcome.)

That’s not to say everyone loved it. Here’s some customer feedback, both good and bad:

“I think a good design is often apparent when you don’t remember what the old one was like. Today, I started using the new UI and so far no troubles at all…Great work!”

“The new design looks very ‘flat’—I don’t know how else to describe it.” (I think this is negative but am not sure.)

“It looks a lot cleaner. Lots of whitespace.”

“I liked the side bar the way it was before. I was able to see everything I could do without clicking.” (Absolutely true, but a trade-off we felt was necessary.)

“Doesn’t look like it’s from the ’90s anymore.”

“I find the new font harder to read.”

“Looks clean, but I am always a little nervous about change and not being able to find something.” (My favorite for its honesty and introspection.)

. . .

Design is never truly done. I don’t anticipate another visual change of this magnitude for a while, but we will continue to evolve and polish what we have. We’ll tweak colors and styles to ensure affordances are clear. We’ll extend our system as new design work requires it. And we’ll look at ways the system can bring design and engineering together, such as shared React components between prototypes and production. (Already, Ray has created a set of multi-state Figma components: once you’ve inserted a dropdown in your mockup, you can access any potential permutation via overrides.) We’ll look for the things we missed—icons we removed and need to replace, alignments that aren’t quite right. And we’ll find the time to keep polishing: we were thorough enough that Heap has no truly “dark corners,” but there are a few that could stand to get brighter.

If this project sounded like fun to you, Heap is hiring communications designers and product designers. In joining a nascent team, you’ll be a part of building our design practice and culture from the ground up. We’ve got fascinating problems to solve and smart, humble, quirky people to solve them. Drop me a line!

Thanks to Raymond Liaw, Timery Crawford, and Anojh Gnanachandran for their help in editing and refining this post.